Akhil Sharma! Interview

Akhil Sharma! Interviewon Aug 26, 2019

About The Author

Akhil Sharma was born in Delhi, moving to the United States with his family in 1979. His stories have been published in the New Yorker and Atlantic Monthly, and have been included in The Best American Short Stories and O Henry Prize anthologies. His first novel, An Obedient Father, won the 2001 Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award. He was named one of Granta's 'Best of Young American Novelists' in 2007. His latest novel, Family Life, is heavily based on his own family's experiences coming to America. Aged eight Ajay is fascinated, and sometimes confused, by the wonders that his new home has to offer. His elder brother, Birju, protects him from the bullies who take exception to the novelty of an Indian child when he is not studying hard for the exams that offer him access to a lucrative medical career, resulting in financial comfort for the whole family. When an accident at a swimming pool leaves Birju severely brain-damaged, Ajay tries to remain strong while his father retreats into the oblivion of the bottle and his mother entertains the evermore fanciful rituals of those who claim to have healing powers. Family Life is the unforgettably moving and witty story of a young life turned upside-down by catastrophe, of the hurt and humour that dwells behind every brave face. In this exclusive interview for Foyles, Akhil explains why the novel took twelve and half years to write, why he felt it was better to present his family's story as fiction and why pigeon-holing authors as 'immigrant writers' can warp readers' perception of their work.

The story is very much based on your own family's experiences. Why did you decide to render them as fiction rather than in the form of a memoir?

There were several reasons. First I think I can be braver and more honest when I can say that what I am writing is a novel. If I had written a memoir, I would have felt as if my parents and everybody who makes up a part of the novel was standing around my desk as I was writing.

Also as important, I know how to write fiction while I don't know how to write non-fiction. I know how to use the tools of fiction. In a memoir I would have felt uncomfortable writing dialogue because I can't remember exactly what people said all those decades ago. I would have felt that it was dishonest to collapse time or combine characters because this was taking things out of context. In a memoir I would also have felt obligated to include things which were objectively true and important to the experience of taking care of my brother but whose inclusion would have changed the nature of the novel. For example, like most children I was often intensely bored. Writing about boredom and reading about it can be tedious, however.

The book took you twelve and a half years to write. What was the biggest turning point for you in the writing process?

The reality is that all those years can be felt in the book and so were needed for the book. The fact that there are so many strange details has to do with my spending so much time with the material.

The big change in the novel was when I decided to limit the type of sensory details that go into the book. For example, there is very little sound, there is very little smell. The reason I did this was because the novel does not have a strong plot. The novel does not have a plot in the sense of A causes B and then B causes C. Instead, A happens and then B follows and F also occurs. This absence of plot made it hard to propel the reader into and out of scenes. Thinning out reality caused there to be less friction as the reader enters and exits scenes.

In earlier drafts you tried writing the story from a number of different points of view. Why did you ultimately settle upon narration by Ajay?

I wrote the book in third person from Ajay's point of view and then from the mother's and father's point of view. At some point I switched it to Ajay's first person narrative. The reason I switched it from third person to first is that third person narratives consume plot at a different pace than first person. While with a first person, the 'I' is always being effected and so something is always at risk, with a third person the significance of an event needs to be justified and so the event needs to be of greater import. This creates a bias in the narrative for either a tighter time frame or more dramatic action.

When I wrote the narrative from the point of view of the parents, I found myself being tugged out of the family circle. Because the parents had greater choices and the situation inside the family is so difficult, the narrative wanted to force me to let the characters use the choices they had and leave the static and difficult situation. This caused the focus of the narrative to shift away from what it is like for this family to take care of someone ill.

Despite the tragedy at the heart of the story, there is great levity at times. Did you find it difficult to find a balance between these two emotions?

I am glad you noticed the humor. To me life is full of laughter, life is full of joy. Any attempt to capture the world must include these things to be accurate. I did have to watch the narrative to see how the reader might be responding to the events in the novel.

Family, of a very different nature, was also at the heart of your first novel, An Obedient Father. Do you think it's essential to know something of a character's family or upbringing to bring them fully to life?

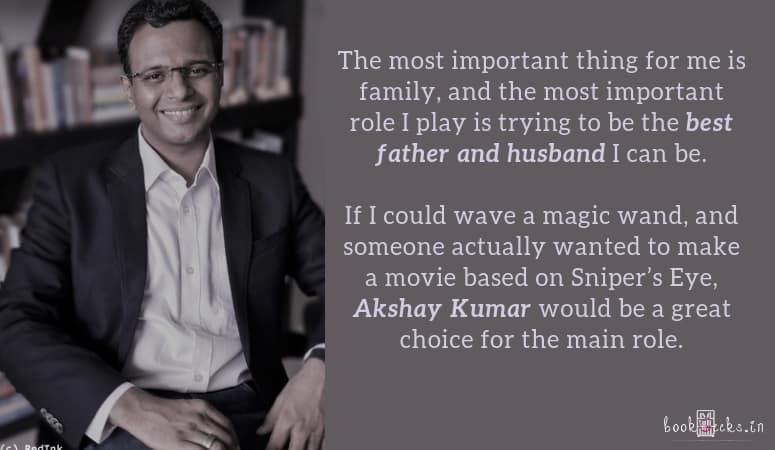

The most important thing for any sane human being is the people in his or her life. Because this is usually family, it seems necessary to write about family.

I am not sure, though, whether it is necessary to describe a character's family or even have a fully fleshed out idea of his family to conjure up the character. If I look at the people I know well, they tend to be very different from their siblings. Our families play a role in who we are, but this is not all that we are.

Are you concerned about being pigeon-holed as an immigrant writer, given how controversial the topics of race and immigration have become?

Thank you for asking this question. It shows that sensitivities about the topic are growing. I want to be seen as a writer and not as an immigrant writer. To me this is no different from wanting to be seen as a human being and not as an Indian.

To say that someone is an immigrant writer is to define the writer in opposition to something else, the dominant culture usually. To say that a writer is a writer and not an immigrant writer is to open yourself to all the things that the person might have to say instead of a having a pre-conceived notion as to what import his words might carry.

Given the semi-autobiographical nature of the book, what has been your family's response?

My parents have not read the book. My mother actually recently asked my permission to not read it. She said that she did not want to return to that period of her life. I said that this was fine. A part of me was even relieved. I love my parents. I would do anything for them. I love them with all their flaws. My parents, however, might see themselves being represented as ordinary people and feel like they have lost face and so I am glad for them to not read it.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.